replyr Join Controller

This note describes a useful tool we call a “join controller” (and is part of our “R and Big Data” series, please see here for the introduction).

This system has largely been replaced by the rquery equivalent.

When working on real world predictive modeling tasks in production, the ability to join data and document how you join data is paramount. There are very strong reasons to organize production data in something resembling one of the Codd normal forms. However, for machine learning we need a fully denormalized form (all columns populated into a single to ready to go row, no matter what their provenance, keying, or stride).

This is not an essential difficulty as in relational data systems moving between these forms can be done by joining, and data stores such as PostgreSQL or Apache Spark are designed to provide powerful join capabilities.

However there are some inessential (in that they can be avoided) but substantial difficulties in managing and documenting long join plans. It is not uncommon to have to join 7 or more tables to get an analysis ready. This at first seems trivial, but once you add in the important tasks of narrowing tables (eliminating columns not used later) and disambiguating column names (ensuring unique names after the join) the documentation and work can become substantial. Specifying the join process directly in R code leads to hard to manage, hard to inspect, and hard to share spaghetti code (even when using a high-level data abstraction such as dplyr).

If you have done non-trivial work with production data you have seen this pain point.

The fix is to apply the following principles:

- Anything long, repetitive, and tedious should not be done directly.

- Moving specification out of code and into data is of huge benefit.

- A common special case can be treated separately, as that documents intent.

To supply such a solution the development version of replyr now supplies a item called a “join controller” under the method replyr::executeLeftJoinPlan().

This is easiest to explain through a concrete example, which is what we will do here.

First let’s load the needed packages.

# load packages suppressPackageStartupMessages(library("dplyr"))

## Warning: replacing previous import 'vctrs::data_frame' by 'tibble::data_frame'

## when loading 'dplyr'packageVersion("dplyr")

## [1] '1.0.1'## Loading required package: wrapr##

## Attaching package: 'wrapr'## The following object is masked from 'package:dplyr':

##

## coalescepackageVersion("replyr")

## [1] '1.0.5'execute_vignette <- requireNamespace("RSQLite", quietly = TRUE) && requireNamespace("igraph", quietly = TRUE) && requireNamespace("DiagrammeR", quietly = TRUE)

Now let’s load some notional example data. For our example we have:

- One primary table of measurements (called “

meas1”) keyed byidanddate. - A fact table that maps

ids to patient names (called “names”, and keyed byid). - A second table of additional measurements (called “

meas2”) That we consider “nice to have.” That is: rows missing from this table should not censor-outmeas1rows, and additional rows found here should not be included in the analysis.

The data is given below:

# load notional example data my_db <- DBI::dbConnect(RSQLite::SQLite(), ":memory:") RSQLite::initExtension(my_db) # example data replyr_copy_to(my_db, data.frame(id= c(1,1,2,2), date= c(1,2,1,2), weight= c(200, 180, 98, 120), height= c(60, 54, 12, 14)), 'meas1_train') replyr_copy_to(my_db, data.frame(id= seq_len(length(letters)), name= letters, stringsAsFactors=FALSE), 'names_facts') replyr_copy_to(my_db, data.frame(pid= c(2,3), date= c(2,2), weight= c(105, 110), width= 1), 'meas2_train')

An important (and very neglected) step in data science tasks is documenting roles of tables, especially their key-structure (which we also call “stride” in the sense it describes how you move from row to row). replyr::tableDescription() is a function that builds an initial description of the tables. (Note: replyr::tableDescription() is misspelled in the current release version of replyr, we have fixed this in dev).

# map from abstract names to realized names trainTables <- data_frame(tableName = c('meas1', 'names', 'meas2'), concreteName = c('meas1_train', 'names_facts', 'meas2_train'))

## Warning: `data_frame()` is deprecated as of tibble 1.1.0.

## Please use `tibble()` instead.

## This warning is displayed once every 8 hours.

## Call `lifecycle::last_warnings()` to see where this warning was generated.# get table references from source by concrete names trainTables$handle <- lapply(trainTables$concreteName, function(ni) { tbl(my_db, ni) }) # convert to full description table tDesc <- bind_rows( lapply(seq_len(nrow(trainTables)), function(ri) { ni <- trainTables$tableName[[ri]] ti <- trainTables$handle[[ri]] tableDescription(ni, ti) } ) )

tDesc is essentially a slightly enriched version of the data handle concordance described in “Managing Spark data handles in R.” We can take a quick look at the stored simplified summaries:

## # A tibble: 3 x 4

## tableName sourceClass handle isEmpty

## <chr> <chr> <list> <lgl>

## 1 meas1 SQLiteConnection <tbl_SQLC> FALSE

## 2 names SQLiteConnection <tbl_SQLC> FALSE

## 3 meas2 SQLiteConnection <tbl_SQLC> FALSEprint(tDesc$columns)

## [[1]]

## [1] "id" "date" "weight" "height"

##

## [[2]]

## [1] "id" "name"

##

## [[3]]

## [1] "pid" "date" "weight" "width"print(tDesc$colClass)

## [[1]]

## id date weight height

## "numeric" "numeric" "numeric" "numeric"

##

## [[2]]

## id name

## "integer" "character"

##

## [[3]]

## pid date weight width

## "numeric" "numeric" "numeric" "numeric"## $meas1

## id date weight height

## "id" "date" "weight" "height"

##

## $names

## id name

## "id" "name"

##

## $meas2

## pid date weight width

## "pid" "date" "weight" "width"tableDescription() produces tables that hold the following:

-

tableName: the abstract name we wish to use for this table. -

handle: the actual data handle (either adata.frameor a handle to a remote data source such asPostgreSQLorSpark). Notice in the example it is of class “tbl_sqlite” or “tbl_dbi” (depending on the version ofdplyr). -

columns: the list of columns in the table. -

keys: a named list mapping abstract key names to table column names. The set of keys together is supposed to uniquely identify rows. -

colClasses: a vector of column classes of the underlying table. -

sourceClass: the declared class of the data source. -

isEmpty: an advisory column indicating if any rows were present when we looked.

The tableName is “abstract” in that it is only used to discuss tables (i.e., it is only ever used as row identifier in this table). The data is actually found through the handle. This is critical in processes where we may need to run the same set of joins twice on different sets of tables (such as building a machine learning model, and then later applying the model to new data).

The intent is to build a detailed join plan (describing order, column selection, and column re-naming) from the tDesc table. We can try this with the supplied function buildJoinPlan(), which in this case tells us our table descriptions are not quite ready to specify a join plan:

tryCatch( buildJoinPlan(tDesc), error = function(e) {e} )

## <simpleError in buildJoinPlan(tDesc): replyr::buildJoinPlan produced plan issue: key col(s) ( name ) not contained in result cols of previous table(s) for table: names>In the above the keys column is wrong in that it claims every column of each table is a table key. The join plan builder noticed this is unsupportable in that when it comes time to join the “names” table not all of the columns that are claimed to be “names” keys are already known from previous tables. That is: the “names$name” column is present in the earlier tables, and so can not be joined on. We can’t check everything, but the join controller tries to “front load” or encounter as many configuration inconsistencies early- before any expensive steps have been started.

The intent is: the user should edit the “tDesc” keys column and share it with partners for criticism. In our case we declare the primary of the measurement tables to be PatientID and MeasurementDate, and the primary key of the names table to be PatientID. Notice we do this by specifying named lists or vectors mapping desired key names to names actually used in the tables.

# declare keys (and give them consistent names) tDesc$keys[[1]] <- c(PatientID= 'id', MeasurementDate= 'date') tDesc$keys[[2]] <- c(PatientID= 'id') tDesc$keys[[3]] <- c(PatientID= 'pid', MeasurementDate= 'date') print(tDesc$keys)

## $meas1

## PatientID MeasurementDate

## "id" "date"

##

## $names

## PatientID

## "id"

##

## $meas2

## PatientID MeasurementDate

## "pid" "date"The above key mapping could then be circulated to partners for comments and help. Notice since this is not R code we can easily share it with non-R users for comment and corrections.

It is worth confirming the keying as as expected (else some rows can reproduce in bad ways during joining). This is a potentially expensive operation, but it can be done as follows:

keysAreUnique(tDesc)

## meas1 names meas2

## TRUE TRUE TRUEOnce we are satisfied with our description of tables we can build a join plan. The join plan is an ordered sequence of left-joins.

In practice, when preparing data for predictive analytics or machine learning there is often a primary table that has exactly the set of rows you want to work over (especially when encountering production star-schemas. By starting joins from this table we can perform most of our transformations using only left-joins. To keep things simple we have only supplied a join controller for this case. This is obviously not the only join pattern needed; but it is the common one.

A join plan can now be built from our table descriptions:

# build the column join plan columnJoinPlan <- buildJoinPlan(tDesc) print(columnJoinPlan %>% select(tableName, sourceColumn, resultColumn, isKey, want))

## # A tibble: 10 x 5

## tableName sourceColumn resultColumn isKey want

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <lgl> <lgl>

## 1 meas1 id PatientID TRUE TRUE

## 2 meas1 date MeasurementDate TRUE TRUE

## 3 meas1 weight meas1_weight FALSE TRUE

## 4 meas1 height height FALSE TRUE

## 5 names id PatientID TRUE TRUE

## 6 names name name FALSE TRUE

## 7 meas2 pid PatientID TRUE TRUE

## 8 meas2 date MeasurementDate TRUE TRUE

## 9 meas2 weight meas2_weight FALSE TRUE

## 10 meas2 width width FALSE TRUEEssentially the join plan is an unnest of the columns from the table descriptions. This was anticipated in our article “Managing Spark Data Handles”.

We then alter the join plan to meet our needs (either through R commands or by exporting the plan to a spreadsheet and editing it there).

Only columns named in the join plan with a value of TRUE in the want column are kept in the join (columns marked isKey must also have want set to TRUE). This is very useful as systems of record often have very wide tables (with hundreds of columns) of which we only want a few columns for analysis.

For example we could decide to exclude the width column by either dropping the row or setting the row’s want column to FALSE.

Since we have edited the join plan it is a good idea to both look at it and also run it through the inspectDescrAndJoinPlan() to look for potential inconsistencies.

# decide we don't want the width column columnJoinPlan$want[columnJoinPlan$resultColumn=='width'] <- FALSE # double check our plan if(!is.null(inspectDescrAndJoinPlan(tDesc, columnJoinPlan))) { stop("bad join plan") } print(columnJoinPlan %>% select(tableName, sourceColumn, resultColumn, isKey, want))

## # A tibble: 10 x 5

## tableName sourceColumn resultColumn isKey want

## <chr> <chr> <chr> <lgl> <lgl>

## 1 meas1 id PatientID TRUE TRUE

## 2 meas1 date MeasurementDate TRUE TRUE

## 3 meas1 weight meas1_weight FALSE TRUE

## 4 meas1 height height FALSE TRUE

## 5 names id PatientID TRUE TRUE

## 6 names name name FALSE TRUE

## 7 meas2 pid PatientID TRUE TRUE

## 8 meas2 date MeasurementDate TRUE TRUE

## 9 meas2 weight meas2_weight FALSE TRUE

## 10 meas2 width width FALSE FALSEThe join plan is the neglected (and often missing) piece of documentation key to non-trivial data science projects. We strongly suggest putting it under source control, and circulating it to project partners for comment.

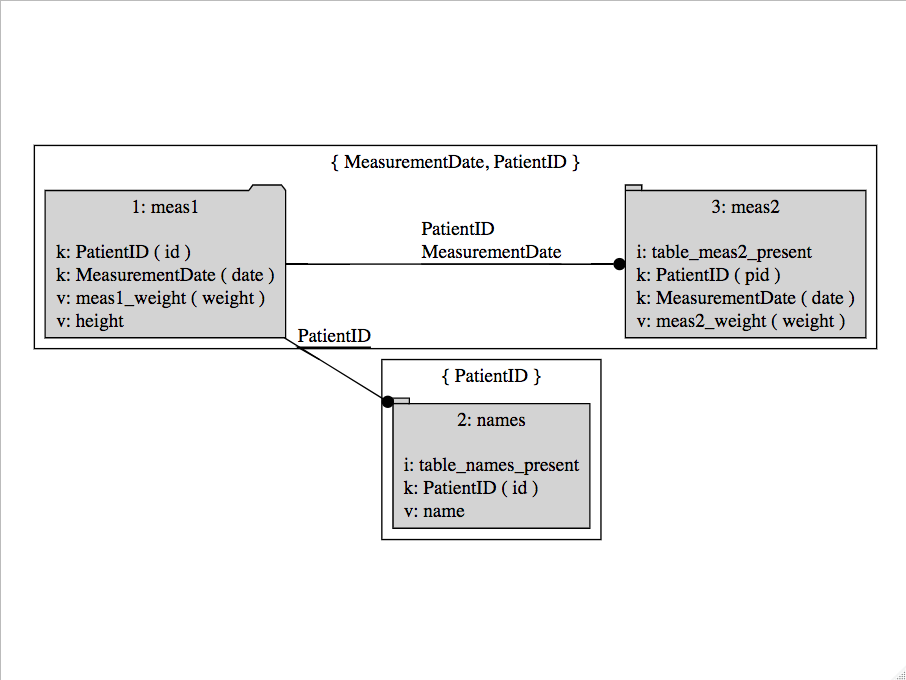

As a diagram the key structure of can be produced as follows:

columnJoinPlan %.>% makeJoinDiagramSpec(.) %.>% DiagrammeR::grViz(.)

Once you have a good join plan executing it is a one-line command with executeLeftJoinPlan() (once you have set up a temp name manager as described in “Managing intermediate results when using R/sparklyr”):

# manage the temp names as in: # http://www.win-vector.com/blog/2017/06/managing-intermediate-results-when-using-rsparklyr/ tempNameGenerator <- mk_tmp_name_source("extmps") # execute the left joins results <- executeLeftJoinPlan(tDesc, columnJoinPlan, verbose= TRUE, tempNameGenerator= tempNameGenerator)

## [1] "start meas1 Sun Sep 6 14:10:22 2020"

## [1] " rename/restrict meas1"

## [1] " 'PatientID' = 'id'"

## [1] " 'MeasurementDate' = 'date'"

## [1] " 'meas1_weight' = 'weight'"

## [1] " 'height' = 'height'"

## [1] " res <- meas1"

## [1] "done meas1 Sun Sep 6 14:10:22 2020"

## [1] "start names Sun Sep 6 14:10:22 2020"

## [1] " rename/restrict names"

## [1] " 'table_names_present' = 'table_names_present'"

## [1] " 'PatientID' = 'id'"

## [1] " 'name' = 'name'"

## [1] " res <- left_join(res, names,"

## [1] " by = c( 'PatientID' ))"

## [1] "done names Sun Sep 6 14:10:22 2020"

## [1] "start meas2 Sun Sep 6 14:10:22 2020"

## [1] " rename/restrict meas2"

## [1] " 'table_meas2_present' = 'table_meas2_present'"

## [1] " 'PatientID' = 'pid'"

## [1] " 'MeasurementDate' = 'date'"

## [1] " 'meas2_weight' = 'weight'"

## [1] " res <- left_join(res, meas2,"

## [1] " by = c( 'PatientID', 'MeasurementDate' ))"

## [1] "done meas2 Sun Sep 6 14:10:22 2020"executeLeftJoinPlan() takes both a table description table (tDesc, keyed by tableName) and the join plan (columnJoinPlan, keyed by tableName and sourceColumn).

The separation of concerns is strong: all details about the intended left-join sequence are taken from the columnJoinPlan, and only the mapping from abstract table names to tables (or table references/handles) is taken from tDesc. This is deliberate design and makes running the same join plan on two different sets of tables (say once for model construction, and later for model application) very easy. tDesc is a runtime entity (as it binds names to live handles, so can’t be serialized: you must save the code steps to produce it; note only the columns tableName and handle are used so there is no point re-editing the keys column after running tableDescription() on new tables) and columnJoinPlan is a durable entity (has only information, not handles).

Basically you:

- Build simple procedures to build up

tDesc. - Work hard to get a good

columnJoinPlan. - Save

columnJoinPlanin source control and re-load it (not re-build it) when you need it. - Re-build new

tDesccompatible with the savedcolumnJoinPlanlater when you need to work with tables (note only the columnstableNameandhandleare used during join execution, so you only need to create those).

As always: the proof is in the pudding. We should look at results:

dplyr::glimpse(results)

## Rows: ??

## Columns: 8

## Database: sqlite 3.30.1 [:memory:]

## $ PatientID <dbl> 1, 1, 2, 2

## $ MeasurementDate <dbl> 1, 2, 1, 2

## $ meas1_weight <dbl> 200, 180, 98, 120

## $ height <dbl> 60, 54, 12, 14

## $ table_names_present <dbl> 1, 1, 1, 1

## $ name <chr> "a", "a", "b", "b"

## $ table_meas2_present <dbl> 0, 0, 0, 1

## $ meas2_weight <dbl> NA, NA, NA, 105Notice the joiner added extra columns of the form table_*_present to show which tables had needed rows. This lets us tell different sorts of missingness apart (value NA as there was no row to join, versus value NA as a NA came from a row) and appropriately coalesce results easily. These columns are also very good for collecting statistics on data coverage, and in business settings often are very useful data quality and data provenance features which can often be directly included in machine learning models.

Also notice the join plan is very specific: every decision (such as what order to operate and how to disambiguate column names) is already explicitly set in the plan. For more on order of operations in left join plans please see “vignette('DependencySorting', package = 'replyr')”.

The executor is then allowed to simply move through the tables left-joining in the order the table names first appear in the plan.

The columnJoinPlan is meant to be re-usable. In particular we can imaging running it to build training data, possibly re-running it to build test/validation data, and re-running it many times to build data we apply the model to. To facilitate this executeLeftJoinPlan() is generous in what it accepts as a tDesc. All it needs from the tDesc argument is a way to map abstract names (tableName) to concrete data realizations (either data.frames or dplyr data handles). So by design executeLeftJoinPlan() accepts either a data.frame (and only looks at the tableName and handle columns) or a map. So the following calls to executeLeftJoinPlan() also work:

# hand build table with parallel tableName and handle columns tTab <- trainTables %>% select(tableName, handle) print(tTab)

## # A tibble: 3 x 2

## tableName handle

## <chr> <list>

## 1 meas1 <tbl_SQLC>

## 2 names <tbl_SQLC>

## 3 meas2 <tbl_SQLC>r <- executeLeftJoinPlan(tTab, columnJoinPlan, verbose= FALSE, tempNameGenerator= tempNameGenerator)

# map of abstract table names to handles tMap = trainTables$handle names(tMap) <- trainTables$tableName r <- executeLeftJoinPlan(tMap, columnJoinPlan, verbose= FALSE, tempNameGenerator= tempNameGenerator)

The above facilities are not intended to re-run the original training data, but to make it very easy to re-apply the columnJoinPlan to new tables (i.e., to support testing/validation and support later model application on future data). Notice in neither case do we use the concrete names of the tables, we map abstract (notional) names to handles.

Having to “join a bunch of tables to get the data into simple rows” is a common step in data science. Therefore you do not want this to be a difficult and undocumented task. By using a join controller you essentially make the documentation the executable specification for the task.

# cleanup DBI::dbDisconnect(my_db)